The freshwater environment

This section of the website is designed to give the reader an introduction to the freshwater environment. It deals with some of the issues that affect river catchments used by migratory salmonids, but does not claim to be exhaustive. Conservation, monitoring and enhancement of freshwater habitats is best done by people on the ground, led by professionals working for public and third sector organisations, increasingly in support of community groups and angling clubs. We hope you find it interesting. If you have any suggestions for ways of improving this section please contact us at director@atlanticsalmontrust.org

Salmon rivers appeal to people for many different reasons. They attract visitors to their banks, and local communities enjoy them in the centre of their lives. They inspire people with their natural beauty and abundance of wildlife. They provide opportunities for relaxation as virtually no other environment can, as their clear waters and healthy flows give people a profound sense of wellbeing. It is part of being human that clean-flowing water can make a spiritual contribution to our lives, and that rivers are able to instill in us a powerful sense of peace and tranquility. If we include in these unmeasurable benefits the presence of wild salmon and trout, which are themselves indicators of a healthy environment, it is easy to appreciate why Atlantic salmon were treated with mystical awe by ancient cultures in all the north Atantic countries into which they migrate. That sense of wonder continues to this day. People who live near a salmon river share awareness of the presence of these fish regardless of whether or not they have a direct connection with them socially or ecomomically. Salmon have a place deep in our culture, to which our legislators would be wise to pay heed.

The River Spey at Knockando in the Spring. (Photo TA)

Big rivers, like the Tay, Dee and Spey, as shown in these photographs are the main stems of their river catchments and represent the qualities and issues of every contributing flow from the highest upland burns to the low ground, mid-catchment tributaries. A river catchment is much more than a channel through the landscape because the river stem represents the geology and biodiversity of the whole watershed. Watercourses of no more than two metres in width provide a ‘filigree’ network of flows to provide upland tributaries with a reservoir of invertebrates and plant seeds to ensure that, whatever damage is done to the main river by drought, flood or human actions, there is always a reserve of the natural characteristics of the river available for restoration.

The River Tay at Dunkeld in late summer (Photo TA)

An awareness of the importance of the whole catchment, from the highest source of water in the uppermost reaches of the watershed to the meeting of fresh and salt water beyond the tidal zone, is a necessary prequisite for catchment and fishery management, and ultimately for conservation of wild salmon and sea trout.

The River Dee at Potarch in Spring (Photo TA)

Freshwater catchments, birthplace and nursery for salmon & sea trout

Salmon and sea trout are anadromous fish, which means that they are born in fresh water, spend most of their lives at sea and return to fresh water to spawn. The ability of a river catchment to generate sufficient smolts to ensure that each genetically distinct component of the stock of a river meets its Conservation Limit (CL) is the most relevant output measure for fishery managers. The development of the Fisheries and Rivers Trusts network throughout the UK (RAFTS, in Scotland and The Rivers Trusts, in England/Wales) has focussed on natural regeneration of stocks, with the emphasis on habitat restoration and conservation.

Obstructions to migrations of salmon & sea trout require constant monitoring. This photograph shows a damaged roundstone dyke on the South Esk being assessed to determine whether it poses a serious obstruction to the passage of fish.

How do salmon and sea trout use fresh water? The life strategy of anadromous salmonids is to utilise freshwater habitats for returning adult salmon and sea trout to deposit their eggs, and for juveniles to grow, generally over one, two or three years in the UK, to the point where they leave freshwater as smolts to feed in the sea.

So, what properties and characteristics in a catchment do these fish need while they are in the freshwater phase of their life cycle? (The following list provides an overview and makes no claim to be comprehensive).

Near-perfect upper catchment nursery area on the Angus South Esk for salmon and sea trout. The riffle/pool sequence provides habitat for both species, with salmon parr generally requiring shallow riffle. These territorial little fish prefer streamy shallows where line-of-sight separation from other parr is provided by rocks and small boulders. Dappled shade provides sufficient light for photosynthesising aquatic plants and sufficient shade to cool the shallow stream.

Some requirements of salmon and sea trout in the freshwater environment.

- Clean water – freedom from pollution

- Suitable and consistent minimum flows – avoiding over-abstraction

- Sequences of riffle/pool providing varied depths for feeding and high quality refugia

- Access to spawning areas – removal of barriers to migrations

- Suitable spawning locations – cobbles and gravels washed clean of silt

- Streamy, broken-up riffle to provide habitat for salmon fry and parr

- Foliage cover to provide security, shading and cooling

- Prey-food species habitats for all stages of freshwater growth post alevin stage

This short and simplified list of requirements can be seen as cues for managers, or the objectives of effective habitat conservation and enhancement. One of the best summaries of good stream management principles is the Washington State guidance on catchment management, which is well worth using as a practical reference tool.

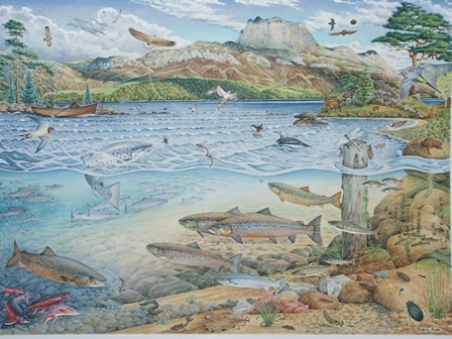

The picture above (courtesy of the Wester Ross Rivers Trust) shows schematically the range of natural biodiversity in Loch Maree. This important west coast ecosystem is the dominant feature of the Ewe catchment and, with its feeder burns and upland tributaries, provides freshwater habitat for salmon and sea trout during the breeding and juvenile stages of their lives.

Managing the freshwater environment

Prior to the arrival of the fisheries and rivers trusts in the 1990s there was little coordination of best habitat management practice around the country. In those days, when effectively it was ‘each river for itself’, AST’s role was to respond to requests for help on a firefighting or ad hoc basis. That has thankfully now changed with the Rivers Trust in England and Wales and RAFTS in Scotland providing an increasing level of professionalism to the task of managing every catchment in the country. This most welcome development has enabled AST to adopt a role that supports the trusts network, and has allowed the AST to turn its focus on the marine phase of the salmon and sea trout lifecycle.

Fishery Management: electro-fishing the riffles in summer water levels to determine densities of salmon and sea trout juveniles as part of stock assessment

At this stage it would be wrong to claim that the trusts network is complete, or that quality of delivery is consistent, but there are already some impressive examples of good fishery and river management practice in England’s West Country, the Northwest of England and in the East of Scotland (Rivers Tweed and Dee)

River Frome water board weir (above) prior to construction of the fish pass (below). The configuration of the weir provided a serious obstacle to the passage of salmon and sea trout. Fortunately, as the result of a campaign by local people with the Frome and Piddle Rivers Trust, funds were raised and the support of the Environment Agency obtained to build a modern fish pass which was completed in 2009. Since then many more fish have been able to access the spawning areas in the upper catchment.

The newly installed fish pass at Louds Mill near Dorchester on the River Frome (above). The modern design of the pass shute, which slows down and breaks up the flow, makes it very easy for salmon and sea trouit to gain access to the upper catchment at most water levels. (TA 2009)

The European Commission’s Water Framework Directive (WFD) and the UK laws suspended from it are the basis for the improvement and sustaining of water quality and freshwater environments throughout the UK. In terms of habitat conservation there is no stronger piece of EU legislation, which has already done more for cleaning up the aquatic environment than anything done previously. While it is undeniable that there is a long way to go before the WFD vision is achieved, it is fair to claim that better water quality, promoting ‘natural’ catchment morphology and restrictions on abstraction and point & diffuse pollution have already produced results in the form of migratory salmonids returning to river catchments where, in some cases they have been absent for many decades. The WFD is underpinned by scientific methodology and monitoring. EU member states are obliged to report at regular intervals on the exacting demands of the Directive, with penalties for governments that fail to comply.

We should recognise that the WFD is a ‘framework’ directive, and as such does not specifically include small streams (the ‘filigree network’ of tiny tributaries) which are referred to below, with respect to their role as biodiversity reservoir for river catchments. We make the point that the management of these sometimes ephemeral sources of water is a vital part of river catchment management.

In 2016 the UK voted to leave the EU in the United Kingdon European Union membership referendum (Brexit). A paper written jointly with other freshwater fisheries related NGOs looked at the implications that this might have on freshwater management in England and Wales. Joint Paper: Brexit, Fisheries and the Water Environment.

Salmon smolts. After 1, 2 or 3 years in fresh water, the length of time depending on the geographical latitude of the catchment or altitude of the nursery section where they lived, these little fish leave the relative security of their home rivers to head out to sea. As they move from fresh to salt water they go through a physiological process called osmoregulation to enable them to retain water and dispose of excess salt.

Biological indicators.There are certain species of plants, invertebrates and animals that can tell us if the aquatic environment is in good condition. Some of these species, such as the brown trout – Salmo trutta L- have been designated as a Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) species. The BAP status for trout – and this includes sea trout of course – enables us to use their presence or absence to monitor water quality. Salmon and trout need clean water to survive. Rivers severely affected by pollution, as for example the River Mersey was until quite recently, cannot provide the habitat needed by both species. When in 1989 the Mersey started to produce adult Atlantic salmon after their absence for many decades it was a signal that water quality had improved to a point where the river could once again support a stock of salmon (and probably migratory trout too).

People & rivers: As indicated in the opening paragraph of this section of the website, the morale effect on communities of knowing that their local river is clean enough to support migrating salmonids is valuable because it activates conservation, wildlife and angling groups to become involved in monitoring and managing their river.

Engaging with stakeholders in the river catchment raises awareness of the value of the river and its tributaries to local communities and encourages their involvement in monitoring and maintaining them in good condition. In an overcrowded country such as the UK, in which most rivers flow through built-up areas it is important that there is public awareness of the damaging effects of domestic and industrial pollution on riparian habitats, water and the wider environment.

They become volunteers working to improve habitats. They become pollution watchdogs, and soon develop into powerful local lobby groups on behalf of the river environment. Volunteer groups, working under the guidance of a professional fishery manager or biologist, soon develop an interest in the science that underpins river management and they can then become citizen scientists.

River catchments:

The freshwater environment is directly affected by human activities within a river catchment. A catchment consists of all land and watercourses within the watershed, and into the sea for three miles beyond the high water mark. The catchment is the best possible unit of management because it is a defined ecosystem dependent on all sources of water within the catchment watershed. In cases of big catchments such as the Wye, Tay, Tweed or Tyne the overall catchment is, for management convenience, sometimes broken down into sub catchments, which share a common mainstem and estuary. In such cases a coordinated overview becomes important when dealing with ecosystem issues such as dealing with invasive species. For smaller catchments such as the Exe, Frome, Gruinard or South Esk the whole catchment can easily be managed as a single unit.

Main Stems, tributaries and small streams

Most people know the name of their local river, and sometimes of its main tributaries, but few people are aware of the importance of the small streams that flow into the river system to make up the whole catchment. The ‘filigree’ network of streams of less than an average 2m in width may not seem important, but even when these rivulets are not big enough to provide spawning or juvenile habitats for fish, or if they dry up in summer months, these tiny watercourses provide vital nutrients, a reservoir of aquatic plant seeds, habitat for invertebrates, small mammals and amphibians on which the whole catchment depends for its biodiversity.

The importance of small streams, where salmon and sea trout spend the juvenile phase of their lives, can benefit from canopies of deciduous trees and foliage providing ‘dappled’ shade and a cooling effect from the heat of the sun, thereby reducing water temperature downstream in the catchment. River managers and biologists are often surprised by the appearance of large sea trout in very small streams, where they deposit their eggs and where their fry and parr grow in the early stages of their lives. A well-managed catchment will have as much emphasis placed on these small tributaries as on larger ones and the main stem of the river. The report on the recent Small Streams Workshop held by IBIS and AST at Carlingford In the Irish Republic summarises some of the issues of this often neglected aspect of riparian management.

A small stream on Hoy in the Orkney Islands. This pristine burn provides excellent spawning and juvenile habitat for sea trout. Very often these little streams, with their own estuaries direct into salt water, enable big sea trout to enter fresh water, spawn and get back to sea within one or two days. Such behaviour emphasises the variable use sea trout make of the freshwater environment. In some rivers, such as the Devonshire Dart, sea trout (or ‘Peel’ as they are called in the West Country) shoal in pools high on Dartmoor, 30 miles from the sea, on both the East and West Dart rivers and, like salmon remain in the river for many months. Not very much is known about how big sea trout use small streams catchments, and this subject is a continuing priority for AST supported research.

Small streams (this is Orkney again) may be reduced to ditch status by straight-line dredging, as has happened to this burn in the recent past. Nonetheless, and despite the damage done by draining the land in this way, these water courses do recover quite quickly. In this case the recovery is well underway as a result of fencing, buffer strips and tree planting. Water flow and quality is good, and there is good refuge, shade from bank foliage, and terrestrial food habitat developing along the banks. Such streams can provide very good spawning and juvenile habitat, mainly for trout.

Catchment Management partnerships

Recognising the importance of all parts of the catchment and the contributions made by water courses of different sizes is the key to good management. Maintaining habitats in the freshwater environment is best done through catchment management because it is the best way opf accessing the diverse skills sets that are needed to deal with a wide range of terrestrial and aquatic issues. The broad approach demanded by managing all influents and effluents within the catchment of a river system engages all stakeholders and should include:

Upland land managers and farmers

Forestry interests

Riparian owners

Fishery managers

Wildlife groups (eg RSPB)

Local council public access and roads

Local council economic development and tourism

Local council infrastructure services

Environmental protection agencies (flooding, water quality, pollutioin monitoring)

Farming liaison groups (e.g. FWAG & LEAF)

Fishery Board

River & fishery trust

Canoeing & rafting interests

Angling associations and tenants

It is important that the Catchment Management Partnership (CMP) avoids becoming another bureaucracy by adding yet more weight to the task of form-filling and sending returns which most farmers and land managers find burdensome. Experience of catchment management shows that the most effective CMPs are based on relationships within an informal structure, with four or five meetings each year.

Successful CMPs lead in the production of a catchment plan, agreed by the partners and finalised after extensive consultation with stakeholder groups in the catchment. A good example is the South Esk Catchment Management Partnership . Ideally there should be a project manager to take forward specific tasks agreed by members. CMPs should be a forum for discussion based on voluntary attendance, and allocating and funding tasks on a case-by-case basis. Usually CMPs do not trade, employ staff or have a persona in law.